Virtual Exhibition

In January 2019, when nine Arizona artists convened in Flagstaff to embark on a weeklong experiential “water science boot camp,” the conditions were anything but parched. Coinciding with the first major snowfall of what was to become one of the snowiest and wettest winters in Flagstaff’s recorded history, the group of artists, led by water experts from across the state, drove through snow, waded through creeks, and immersed themselves in an intensive exploration of the role of water in the typically arid Southwest. But this was not a typical year. The massive precipitation of that winter gave way to the driest summer season on record. The annual summer monsoons that the region depends upon to deliver significant rainfall during July and August didn’t arrive. Arizona was, indeed, parched.

These weather patterns are perhaps artful in themselves, short-term expressions of the long-term severity of a rapidly changing climate. From the snowfall in the San Francisco Peaks to the rain of central Arizona valleys, from abundant flooding to scarcity during prolonged drought, the seemingly unreliability of precipitation is a reminder of the complexities of climate that make the topic of water not only timely, but gravely urgent, to explore, locally and globally, through the vehicle of art. The artists contributing to this exhibition have created work that critically contemplates and reflects upon the presence and absence of water and how it runs through our lives.

During the “boot camp,” the artists learned from scientists, policy makers, and conservationists about regional freshwater ecosystems and threats, the biogeography of the Colorado River and adaptive management, dam removal, water resource management, conflicts pertaining to water rights and issues of contamination, and other topics related to water. Field-trips took them to Gray Mountain; Glen Canyon Dam; Navajo Generating Station; and Tuba City, for presentations by the Navajo

Department of Water Resources and perspectives by Navajo and Hopi representatives and activists. They traveled to Fossil Creek to wade in the water while learning about dam removal and ecosystem rehabilitation. They toured the Scottsdale Water Campus and their state-of-the-art wastewater treatment facility that provides reclaimed water, in part, to golf courses. Finally, they visited the Verde River before returning back upstream to Flagstaff.

These firsthand experiences revealed deep disparities pertaining to water, driven by climate change and population increases. Seasonal flood episodes scour and clean rivers and streams, and organisms are dependent on these cycles. Dams, built for hydropower and water storage, compete with natural bursts and floods. Most of the diverted water from the Colorado River flows to agricultural uses (primarily lettuce) in California and Yuma. Less goes to domestic use (drinking, lawns) in Phoenix and Los Angeles. And NONE goes to the Indigenous communities (for safe drinking, cooking, and bathing) inhabiting the very land through which the water is pumped and piped.

These paradoxes are geographically separated by space, and further diluted by conflicting media reports and competing public and private interests. It is the role of this exhibition to bring the issues into close proximity. Over the course of eighteen months following the “boot camp,” these artists created new works, informed by scientific and cultural inquiry, that reflect diverse perspectives and provocative insight into our intricate relationship with water in our natural, cultural, and political landscapes.

Julie Comnick

Curator

Traveling Between Art and Science

Jane C. Marks, PhD

Professor, Freshwater Sciences

Northern Arizona University

What a journey! The steering committee of scientists, managers, and environmental advocates had one week to spend with artists exploring water in the southwest. We decided to steer away from graphs and figures and classroom presentations. Turning instead to field trips because artists, like field scientists, want to be immersed in their study system. We embarked on a road trip visiting sites that visibly illustrate water tradeoffs and conflicts. We engaged with three interrelated themes: Water Policy & Management, Water Justice & Water for Nature.

How do you see water policy and management? By visiting the infrastructure. Dams, diversions, and water treatment plants reflect investments and priorities. We discussed problems that infrastructure solves and problems it creates. We began at the Glen Canyon Dam, a large iconic dam that depicts the last century of water policy. The Colorado River built the west. Phoenix, Tucson, Denver, Los Angeles & Las Vegas all use water diverted from the Colorado. The Colorado fuels the country’s most productive agriculture. If you eat a salad in the winter, you are drinking from the Colorado River. We wouldn’t be able to grow lettuce and citrus without large dams. A common misperception is that these large dams are primarily for hydropower. In the arid southwest, dams are used to store and move water where and when people want it. Dams and diversions allow for food production, drinking water, swimming pools & golf courses, but we lose free flowing rivers and the plants and animals that live there. We don’t want scurvy but we also want wildlands and nature.

How do you see environmental justice? By talking with people and finding out how they get and use water. In 2010, the United Nations passed a resolution formally recognizing the right to water and sanitation for all people acknowledging that clean drinking water and sanitation are essential to the realization of all human rights. Although much of Colorado River’s watershed includes native lands, 30% of people don’t have safe drinking water. We talked with people who haul water because they don’t have running water in their homes. We met with Ernest Tahoe, a Hopi elder, who leads a citizen group bringing water filters to people whose water has unsafe levels of arsenic and uranium. We contrasted what we saw on the reservation with a visit to the Scottsdale Water Campus, one of the richest communities in Arizona, where people can afford state of the art wastewater treatment to use reclaimed water for golf courses. It did not escape our olfactory systems that money can buy less odor. We talked about water pricing and the inequities of water being cheap for agriculture but expensive for households on the reservation. But we also discussed pricing as a future tool for sparking innovation in water use efficiency.

How do you see water for nature? By comparing altered waterways with natural ecosystems. In Phoenix, we saw Colorado River water diverted to the Central Arizona Project – a human made canal that looks nothing like a river. Most water in the southwest runs through artificial channels or highly regulated rivers. We talked about what rivers need to be healthy ecosystems. Arizona only has two wild and scenic rivers, where water runs free – the Upper Verde and Fossil Creek. An afternoon at Fossil Creek provided an opportunity for artists to relax and enjoy nature and understand what we give up when we control water. Fossil Creek is a restoration success story, a place where people used science and technology to conserve nature. How do you restore a river? Rivers need natural flow regimes with periods of high and low flow that allow water to create complex channels with riffles, pools, eddy’s and backwaters. Dirty ditches are unidimensional. Rivers have curves and complexity. Complexity breeds diversity of plants and animals. In restoring Fossil Creek managers didn’t just remove the large hydropower infrastructure but they also brought back natural flow regimes so that algae, the microscopic organisms that fuel the food web could proliferate. Natural rivers also need riparian zones; trees and plants that grow along the banks. Plants shade the river buffering heat waves and in the autumn as leaves change color and fall into rivers they feed the mayflies, caddisflies and dragonflies that feed fish. Insects that fly out of the river feed birds, bats, lizards and frogs. And a few of the insects might bite you, an example of a small tradeoff – you tolerate a little itch in return for a productive web of life.

Parched is a call to action. Water policy in the Southwest is based on water we may no longer have. The science is convincing. Climate change will cause droughts. We want to meet human needs, we want environmental justice and we want to protect rivers. Something needs to give, but we haven’t figured out what. People working to restore rivers or bring clean drinking water to neighbors help us visualize a sustainable path. My hope is that the Parched exhibit inspires you to begin your own road trip towards solutions. Plan for a lot of flat tires.

Hauling Water

Tommy Rock, PhD

On a hot summer day, when the temperature soars above 100 degrees in the arid desert, it’s as if the sun were nearly done making all the water evaporate from the Navajo Nation. The livestock roaming the desert walk with their heads hung down, trying to retreat from the heat. From the desert shrubs there is only a still quietness as they wait for the monsoon. In this unforgiving heat every living being seems drawn to every life-giving oasis for a taste of the refreshing life giver, water.

For you, this means hauling down a washboard dirt road as the vehicle takes a pounding, like what you see in the action movies. The truck takes a relentless pounding but keeps going, all the rattling noise reminding you of a jingle dancer with all those little bells. You know the pickup must keep going as you barrel down the road. The water barrels roll around in the back, rattling and loose with whatever is, or was, in the truck bed. Hoping that the truck doesn’t fall apart, with a half-smirk expression on your face, you jam that “Indian Car” loudly down that road. Even the animals all stop and look toward the god-awful racket. It almost sounds like there’s singing, half-heartedly, among all that screaming.

As the half-day journey nears its end, you see a long line of vehicles ahead in the middle of the day. You pull in behind the last one, wishing you made better life choices, like getting up early and doing this before the sunrise. On the draft of wind that brings a slight chilly breeze through your open truck, you can just hear your elders saying, “I told you to get there early.” You think to yourself: if only my family could drink the spring near my grandparents’ place. If only the water was safe to drink . . .

but you witness these senseless cases of cancer from the uranium-contaminated water, marked with that dreadful yellow-and-black sign, the sign of death in this fragile desert, where water is even more scarce now than ever. You reminisce about your family and friends that passed on.

The line moves ahead, but slowly. There are other things to think about too: the legal agreements and dams and canals that take water from the rivers to the cities and suburbs and big green farms scattered around the lowland deserts, even as so many Native people pray for rain for the corn and have to haul their own water for the household. Thirty percent of Navajo people have to haul unregulated water that’s sometimes contaminated with uranium or arsenic. The assumptions in western society that Native people really didn’t deserve the right to much water because nobody ever saw them using it in a wasteful way. And the equation that says that water can easily be traded for the small pieces of green paper that seem to mean so much. As if the two could be equal.

Just thinking about it all makes you angry. The unforgiving heat makes things a little harder when you can’t escape it.

But as you sit there in your troubled little world, you remember your grandparents’ teaching: you are resilient. Your ancestors have proven that over and over in dealing with the U.S. government. They rose to the occasion. You think to yourself: bring it on. We will be victorious again because we are persistent, motivated, and resilient.

Klee Benally

Storm Patterns No. 2 | Mą’ii No. 4 / The thief

Harmony / Disharmony | Playing Through

In the desert we listen to the land or we cease to exist.

The gathering clouds, the intimate words comprising a prayer. The cartography of memory and song that reveal sacred springs. Digging wells, filling barrels, hauling water. How many generations have walked here, to wear this path? There is a deep earthly intimacy with this life without running water, with these roots.

From this sacred mountain I see desiccated lands replete with uranium-poisoned wells, strangled rivers, aquifer depletion, dying horses, and dry fields. I see golf courses, water parks, wastewater snow, and glistening swimming pools.

I seek to disrupt the flow of whitewashed pretenses and confront the ongoing legacy of colonial violence that views water as an exploitable commodity.

This is a story of harmony and disharmony. Just as water is life, water can also bring its end.

Josh Biggs

Landscapes in Conflict: Surveilling Water Use from Above

In its use for agriculture, development, and recreation, water can be measured in acre-feet. In the desert, water use can be measured in color.

Color palettes for date trees and golf courses bring in different hues and patterns than ocotillo and saguaro. The canals of the Central Arizona Project cut a clean blue path, while the washes and canyons drop into jagged brown shadows. Negative space becomes positive, and fills up with different and more recognizable, repetitive shapes and patterns, once you add water. Where much of our consumption – electricity, oil, gas – is hidden in the folds, the use of water in the Southwest deserts betrays itself in bright blues and greens.

For this project, I wanted to track down and reveal the places where the tension between places with and without water was most visually apparent.

Debra Edgerton

Life Extended

I have heard from our Indigenous people that Water is Life. And I continue to be drawn back to the strength, power, and commodification that the subject of water brings to itself. In my art, I have spoken to the relationship between humans and the forces of water, how we have tried to harness it and how nature always tries to win it back. But my past work spoke to this from a human perspective and the conclusion of the life cycle. My current work focuses on the ecological/biological ramifications of change from a perspective related to Fossil Creek.

For more than 100 years, water from the Verde River and Fossil Creek had been diverted to the power plants at Childs and Irving hydroelectric facilities. However, conservation organizations convinced APS that the restoration of the Fossil Creek’s ecosystem would have a far greater benefit than the continued production at the power plants. In 2005, APS stopped diverting water to these plants to let water once again flow freely through Fossil Creek.

My project entitled Life Extended looks at the beginning stages of the regeneration of the life cycle in and through water. Through microscopic image references, I have created a series of paintings emphasizing the growth of algae in the reclaimed ecosystem at Fossil Creek. Microalgae are primary

producers and are considered to be at the base level of the aquatic food chain. Some are cyanobacteria with a simple cell structure, while some are green algae and diatoms with more complex life forms. The algae I have observed come from the periphyton group (collected from rocks, sticks, sand or aquatic plants.) And the algae at Fossil Creek is one of the first steps in continuing the life cycle of aquatic and human ecosystems. So, Water is Life in so many ways and for so many of us.

Neal Galloway

Ground Water

Flood Lines

By re-appropriating discarded materials into artworks that reference and incorporate the natural world, I attempt to explore our relationship to nature, waste, and our emotional connection to objects and the natural environment. At its core my artwork focuses on the way in which the Earth’s environment and inhabitants are shaped by human consumption. Perhaps few words are better equipped to describe our current relationship with water than “consumption.” Water is regulated, moved, wasted, cleaned, polluted, and distributed according to the appetites and histories of consumption in ways that are incompatible with changing climatic conditions and social realities. The two works I have created for Parched explore this idea from different points of view.

The first, Ground Water, imagines a future in which the environmental reality of water catches up with our antiquated and short-sighted attitudes, habits, and laws. Beyond illustrating a new water reality, Ground Water invites contemplation and challenges viewers to alter our troubling ecological trajectory while evoking eternal life, futility, kitsch, disappointment, and promise.

The second artwork, Flood Lines, is distributed around the gallery as a spatial intervention and is more analytic in nature. In the United States, the quantity of water on large scales is measured in acre-feet—the amount of water needed to fill an acre of land, one foot deep. This nearly unimaginable volume of water consists of 325,851 gallons and is central to the management of water at the national, state, municipal, and corporate level. Flood Lines is a visualization which asks viewers to imagine that the whole volume of the main gallery at the Coconino Center for the Arts is filled with one-hundred dollars’ worth of water purchased at different rates. How much (or little) water can you purchase for $100 if it is delivered to your rural property by truck? How does that amount compare to purchasing water for industrial or agricultural use from the Central Arizona Project (C.A.P.)? How much for golf courses or universities? Embedded in these comparisons are legacies of water distribution systems permeated by inequality, racism, technology, greed, and environmental ignorance.

Marie Gladue

The Healing Dance at Hooghan (Home)

The word parched: I am reminded of how a once-vibrant Dineh (Navajo) community at Big Mountain disappeared due to relocation of their families. Over 55 years, some Dineh continue to resist the relocation, remaining on the land. Many are still living without water to their homes, no electricity, or decent safe roads. They are dealing with drought and hauling water on a daily basis.

In exchange, the land was opened for access to free water and high-grade coal at pennies a ton. It was a cheap deal, in providing transportation of coal, supplying electricity, and diverting water from the Little Colorado River to the cities of Phoenix and Tucson. It was a cheap deal to build big cities in a hot desert that had no water.

Imagine parched. I visualize the disappearance of the once seeping springs that fed the life of the area. The drawdown of Ice Age female life water (the Navajo aquifer) that lies deep within the Female Goddess (Black Mesa), our mother. Peabody Coal sucking her lifeline dry, pumping, slurring her with coal to the Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada. Our sacred water parched!

In our resiliency to survive, we must understand that the lateral violence that stems from western capitalism and is happening in our communities is also happening to the land, water, and air. The Healing Dance at Hooghan (Home) is about healing the land, water, air, and people. Healing the story of brokenness, for all people. And coming back to what is sustainable. If we do not revitalize our hearts to reawaken to the importance of social kinship and responsibility to all life, we will not survive as a continued evolution. In turn our parched souls will die of thirst.

Delisa Myles

Saurian Memory

In this apocalyptic love story I create a new myth set in the not-too-distant, and not-too-improbable, worst case scenario future.

The scene is set in the time after the great droughts and famines, after the obliterating fires and floods, the mass migrations and extinctions, after the sky collapsed and the rivers ran dry. This is long after endless holes were punched in the earth and all extractable reserves for energy, farming and war were sucked dry. It is after the formidable water crusades, which left planet Earth an unrecognizable wasteland.

In the new beginning Earth is a perfect white sphere, a planet of mute ash, or was it snow? Or perhaps radioactive fallout? We can’t know for certain, there were no witnesses.

The mythological creature I embody is Serpent River Woman, guardian of waters and protector of portals between earthly and spiritual realms. She holds the blueprint and memory for all life on Earth, as water is the pilot for all beings.

She was sealed in the last vestiges of ice deep in the Earth, suspended in a coma of frozen sleep. The epoch of sinking, receding and condensing had reached its nadir and with a spark of warmth she begins to melt and rise. As she rises she hears the persistent but quiet cries of a small girl child who sheds incessant tears as she spins in endless circles.

The love story begins when Serpent River Woman’s icy home begins to melt, the skin of her previous life molts as she emerges into the blinding light of the new life.

In this dancing myth I explore the territory and questions….

What are the many voices through which water speaks? What are the messages that come to us from the distant future? How can our sorrow and love for the Earth save us? How do we perform sacred Water Rites that honor water as the true carrier and currency of life? How much water is left? For how many people? Who goes thirsty? How many rivers can we live without? Where do the songs of extinct birds go? Is there a way to curb the mad train of our runaway destruction? Is there a way to a different future?

Delisa Myles – Concept and Dancer

Shawn Skabelund – Sculptural Installation

Amanda Kapp – Dance Film

Anastazia Louise/Bad Unkl Sista – Costume Designer

Sound After Silence – Music

Shawn Skabelund

The Bodies Gone, the Purchases Made

Artist Statement

In her opening remarks at NAU’s Climate 2020 Conference, Ann Marie Chischilly, Director of the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals, stated that if we don’t voice our opposition to the National Football League’s Washington R…’s use of their current team name, then all of our actions and all of our words concerning the climate crisis would be meaningless and hollow.

As a Parched artist, I had been thinking nearly the exact same thing as Ms. Chischilly as I drove down to participate in the conference that morning. I left realizing that if we are to take the climate crisis seriously, we must be willing to sacrifice our individual desires for the good of the community, the Earth, and the smaller bodies of the Other.

The purity of snow softens the forms covering the blemishes of the marks made by humans – the topographies of overburden, the stumps of destruction. Its whiteness blankets the autumnal changes that lead to the symbolic death of winter, in preparation for the resurrection of spring. But what if those reclaimed waters made into snow still contain “compounds of emerging concern,” pharmaceuticals, personal care products and endocrine disrupters, compounds that may be safe for human health and consumption, but not for the smaller soft bodies of amphibians emerging from Spring’s thawed earth? Like the “germ laden” blankets given to Aztecs in Cortez’s conquest or the “smallpox laced” blankets issued to the Lenape in order to “inoculate the bastards,” is there a difference in the knowing way we pipe effluent up onto the slopes of the San Francisco Peaks and the lebensraum of the Third Reich?

As we go about our daily affairs we are constantly and consistently faced with a set of choices to make, actions to pursue. Each of these decisions has the potential to affect the greater good of our society and the ecosystems we inhabit. Our choices reverberate over time.

In Flagstaff, we see selfish desires being played out on a landscape of spirituality. Reclaimed waste water, effluent waters, piped back up onto the San Francisco Peaks, to satisfy our human desires and wants. Our waste will, over time, enter the bodies of Other creatures: frogs, toads, and salamanders.

Fait accompli, for us and for these species? Or are we willing to change our desires and rethink our cleverness, our economic systems, for the good of the whole?

Glory Tacheenie-Campoy

“Adáádáá’ nizhónîgo nahóółtá (Yesterday we had a beautiful rain)

Artist Statement

The Diné Creation or Emergence story is about a diverse community of lifeforms, both mortals and immortals, who are seeking a sustainable and healthier world to live in. After traveling or migrating through several worlds, they finally settle in the world we live in today, with all of its natural resources like water, plants, climate, and healthy, breathable air that allows for our sustainable existence. With their accumulated knowledge from encounters with powerful spirits, gods, goddesses, monsters, and humans attempt to live together on the planet Earth.

Water is precious, sacred, and a powerful natural resource. Without water life is not sustainable. Today not everyone has access to clean drinking water. Drought, climate change, and increased population have created a higher demand for water.

Southwest tribal governments and their members are collaborating with universities (e.g. NAU, ASU, U of A, Diné College) scientists, environmentalists, nonprofits, and local, state, and federal governments to mitigate climate change.

Throughout the country, some Indigenous tribal communities pray for rain at ceremonies asking the forces of nature, and its deities, gods, and goddesses for rain, to sustain life on Earth as they have since time immemorial.

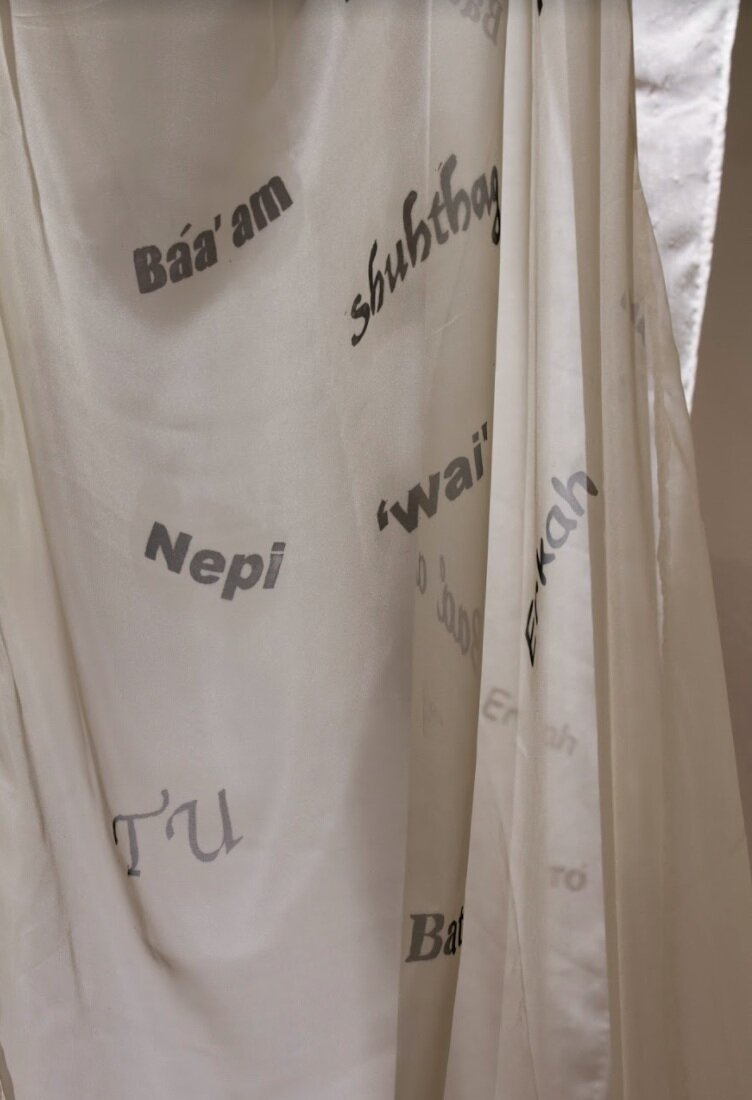

These eight clouds and rain showers are inspired by the creation or emergence stories of the Diné people, who believe that Earth is our mother, and that we must take care of her so she can sustain us all for generations to come.

Printed on fabric are a few Indigenous words for water.

Kathleen Velo

Water Flow: Hopi Reservation

Artist Statement

The images in my series, Water Flow: Hopi Reservation, were created under water, using arsenic-tainted as well as filtered water collected from the Hopi reservation in northern Arizona. These underwater photograms are an artistic interpretation of a visual comparison between the arsenic-tainted water, the filtered water available to the Hopi people, and Flagstaff tap water.

In the desert Southwest, we are increasingly concerned about the quantity of water. Extended droughts, overuse by agriculture and ever-growing metropolitan areas, and recreational use drain our rivers and reservoirs. However, the quality of available water is as much of a concern. Much of the water available is contaminated with pollutants from agriculture, mining, pharmaceuticals, industrial and recreation uses. The situation is even worse for indigenous populations.

Approximately 75 percent of the Hopi population gets their drinking water from wells contaminated with exceedingly high levels of arsenic, as well as uranium. Arsenic levels in the groundwater on the Hopi Reservation are two to three times greater than EPA limits due to declining water levels, and exacerbated by excessive water use by the mining industry; there are also high levels of uranium in the water from mining use. For the past few years, Ernest Taho, a Hopi Elder, has been working with the Black Mesa Trust to bring untainted water to homes on the reservation. Mr. Taho made it possible for me to collect water from different sources on the reservation, with the intention of helping to raise awareness of the inferior quality of water available to residents there.

To create the photograms, I work in total darkness and submerge color photographic paper in water collected from specific locations on the reservation. Once the paper is completely under water, at the right moment, the paper is briefly exposed to a light source to create a photogram of the water contents and movement. The alchemy of photographic emulsion combined with the minerals, salts, pollutants, and other elements in the water create a unique documentation of water contents. The images I create are not science, but a visual representation of water quality.

Carving

Dissected, crenelated, split and gouged, hzome of hoodoo and arroyo, captured drainage and gooseneck, dry wash and box canyon and hanging waterfall, the uplands of the Southwest are etched by the memory of all the waters that have passed through and over them in the long past, seeping their way through the tiniest of earth pores, storming through new-cut gullies, sheeting across some flat expanse after a cloudburst. Water’s busy, relentless, pulsing with energy aching to be spent as it seeks the best way down toward its culmination—for now—in the sea, obeying no one for long but gravity. Give it enough time, and it will move mountains. Snowmelt seeps its way into a sunny-side canyon crevice, refreezes, and crack—a new boulder is on the loose, shedding fragments of sand, pulverizing the smaller rocks below it, tearing hell out of the cliffrose and acacia branches, tumbling down to where a flash flood will someday roll it into a river, leaving a lingering scent of dust in the abruptly still air.

Sometimes the work is more subtle, like the slow chemical wearing-away of limestone until a sinkhole gives way, or the steady drip of a spring that over the millennia wears out its own secluded canyon alcove or builds up intricate natural dams. And when you look out from a high point you can see the dendritic patterns of gravelly washes echoing one another as they branch ever more finely into the bajadas: a diagram of how gravity plays with the land.

Dry country, some say. It’s true, but in the same way that cooking a sauce down increases its flavor, or spending time together rarifies a love: every bit more pressure from the strong sun, every gust of hot wind, increases the urgency of what water is up to. Every bit of its work matters all the more. Bear witness to its progress: you might be looking at a desert plain, a forest, a mountain, a canyon, a hilly tract of junipers—no matter. Each retains marks of all those ghost waters, the drizzles and deluges and whomping snowfalls of long ago. Like an ancient rock carving that disappears almost imperceptibly into its background of desert varnish over countless human generations, even the most achingly dry landscape still shows the traces of all the rain and snow and drip-off and floodwater that made its way there in the past.

People have always studied these patterns, have watched living water to see how it spreads across a field, pulses through a mainly dry wash, backtracks on itself in an eddy, disappears down through its own mudhole in the days after a storm. It’s hard to look away. A puddle or creek, a stick, a child’s hands and feet: it’s enough for an afternoon. And from the study of living water we’ve learned to identify and appreciate the work of waters past and present. It’s no wonder that we can look at the patterns of how water has flowed and find beauty in them, and the beginnings of art: surely the evocative rhythms of erosion were among those that first inspired humans long ago to create their own patterns, brim-full of meaning.

Volume

Water is uncompromising in how it fills space. Swelling and pushing, it insists on the room it needs. Try to boil it down to some essence, and it vanishes. Freeze it into immobility, and it will bust out of whatever container you’ve planned for it. Interrupt its flow, and gravity will carry it through before too long.

We insist on what we think is ours too, and have more trouble compromising than we ought to. Water’s for fighting, they’ve long said in the West, and it’s true that wrangling about it can wedge people apart as mercilessly as it frost-heaves a boulder into a canyon. We have learned to parcel the living flow out into measurable gallons and cubic feet and acre-feet and because we can measure we can divide and because we can divide we can dispute. We can reckon how much a family needs, or a field, or a city. We can calculate precisely how much electricity or money it takes to lift a gallon of water up out of the earth, or over a mountain. We can buy and sell, negotiate and litigate. We can dirty it and, given enough money or time or wisdom, clean it up again. We have a lot of experience intervening in the water cycle—at least in how to move and use the water as it passes by. But too often we forget that nature needs its own share.

On a hot day it’s easy to feel the water cycle. We can watch the squash leaves wilting in the afternoon sun, witness how the hot wind of June cracks the earth and our skin alike, feel the thirst rising. Drink up: we have learned to understand the pace of this precision dance that water carries on with temperature, to put numbers on how energy is the only thing that can move water to rise up against gravity. But now there’s new math to be done, for as the planet has warmed the cycling of water changes. Rain comes instead of snow; the thirsty sky claims water back more quickly as temperatures rise; plants need to sip more from the soil in order to stay alive.

The result is that the rivers of the Southwest carry less water now than they used to. Long stretched thin by water diversions and the pumping of groundwater that feeds them, the Colorado and the Verde and many others are becoming slimmer still. The flow of the Colorado has declined by about 20 percent since the beginning of this century. Arizona officials have responded with a hard-wrangled response called a Drought Continency Plan that lays out who needs to turn off the taps as water levels in the river’s reservoirs continue to drop. It’s a start. But the word drought typically implies a dry spell that will end. What’s new in our new climate math is that the drying trend is much more likely to get worse than to get better. Climate models project that the same pressures will continue to grow, reducing the flow of the Colorado by perhaps another 30 percent in the next 30 years. As summers grow hotter, winters shorter, the old ideas about how much water we have available to use are getting very old very quickly.

Purity

Deep inside a Japanese mountain is a vast chamber filled with some of the cleanest water on Earth. Regularly filtered and bombarded by life-killing ultraviolet light, it has to be pure because the water is there to help record the passage of subatomic particles that might teach astronomers about distant supernova explosions.

Here’s the thing: the water’s so pure that it’s dangerous. Hungry to leach organic materials from anything it can, it would dissolve any living material that comes into contact. This is not water you’d want in your glass, or your shower, or your garden. So though we crave pure water it’s not a simple matter of wanting a substance that can be measured as nothing more than two atoms of hydrogen bonded to one of oxygen. Purity’s a lot more complicated than that. Water wants to bond. Typically rain or snow doesn’t even form until water molecules gather around some particle of minerals and organic matter floating in the atmosphere. Airborne salt will do; so will bacteria; so will all manner of soot and pollutants produced by humans. On its way down, a raindrop gloms on to more stuff: minerals, dust, microbes. Once it meets the ground, it picks up even more companions. The clearest mountain stream is already thick with life, the purest driven snow already doused with other molecules.

Water is life, they say, and the trick is that for the sake of life water has to have just the right level of purity—and “the right level” begs the question, for whom? for what? What’s fine for a carp is going to seem much too murky to a trout. Some plants can stand saline water that would kill a person. Scientists can measure purity in a lab, determine whether the water is sufficiently free of arsenic and bacteria and pesticides so that we can safely drink it, prescribe treatments that will take out most of what we should avoid. In many waters, on the surface or underground, they can find small but worrisome levels of pharmaceuticals and other human-made substances that wastewater treatment generally doesn’t remove. Water’s eagerness to tie itself to other compounds doesn’t always serve it—or us, or other plants and animals—in good stead.

On the space station and in a few water-starved communities around the world, people drink purified water that’s gone through the cleaning process often snarkily called “toilet to tap.” It’s a refined version of the filtering that goes on in nature, for animals’ waste is part of the water cycle too. Many people don’t like the idea, finding it impure, even if water that’s been thoroughly treated is according to the lab far cleaner than what comes out of the river. Because purity exists in the eye and the mind and the heart as much as it does in lab measurements. Because purity is a matter of understanding what water means to us in a way that transcends dollars. Because purity is ultimately a sort of balance: a confluence of water with the values that we use to assess it.

Flow

Maybe a molecule of water could fall in the mountains and gurgle down the Colorado River and all the way to the sea without getting tied up with anything alive—without getting its hands dirty, so to speak. Maybe, but unlikely. Water might be on its perennial way downhill, but it’s easily diverted, hungry for engagement. It doesn’t mind being corralled along the way, dabbled up by ducks or sparrows, slurped by a thirsty bighorn, sucked into roots and hurled high into the sky through a ponderosa’s sapwood, tenderly taken in through porous cell membranes. A molecular extrovert, you might say, water looks to enliven something, anything, with its company. In arid country, it has no shortage of eager partners.

Every drop counts, they say, and it’s true of course, for even the tiniest diversion represents an opportunity for microbe and fungus and plant and animal to do their work of respiring and taking in nutrients and reproducing. Without water, none of that happens. The practice of life in a dry place might be defined as stepping into the flow and altering it

in some way, subtle or brash. In the case of our species that might mean weaving a low brushwood barrier that spreads storm runoff out across a broad wash; spacing the cornstalks or fruit trees just so to intercept the rainfall; pooling it for the livestock; opening the acequia headgate and letting gravity do the work of nourishing the fields; pumping it through mountains and across deserts to foster cities. The creeks and springs and rivers spread their influence across the landscape. Think it over a bit, and the demarcation that a river is only the liquid visibly flowing between banks comes to seem a bit strained if not ridiculous. How can you separate the flowing liquid from the identical molecules that have been borrowed by the willows along its banks, by the caterpillars that eat the willow leaves, by the birds that feast on the caterpillars, by the field nestled in the upper reaches of the floodplain? And what about the blackbrush higher up, nestled among dry rocks but living off the snowmelt it intercepts on its downward path? It’s a watershed’s collective flow, moving through the rocks, through the soil, through myriad living things, that constitutes a river.

And like any extrovert water draws attention to itself. Around here it has a magnetic hold on the senses, calling to us with its faint drip, drip from a canyon spring, waving as sunlight dances off its turbulent skin in a river rapid, washing in on a gust of wind that says a summer storm is on its way. “If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water,” wrote the naturalist Loren Eiseley. Except that the magic is not contained at all. The magic is in water communicating its presence to everyone and everything around. The magic exists in the endless relationships that water throws around itself. The magic lies in water interacting not only with tongues and throats and bellies, but with eyes and ears, hearts and souls.

The Parched documentary tells the story of the creation of the art exhibit- Parched: The Art of Water in the Southwest – which explores the complexities of water in the context of climate change and increasing demands on water. Nine regional artists participated in a comprehensive education program led by scientists, managers, and environmental advocates and spent a year creating original art pieces that are unified into one exhibit. Parched reflects the conflicting demands on water for agriculture, recreation, households and nature. Parched highlights how social and cultural inequities are manifested through current water policies and practices. With the Covid-19 pandemic challenging traditional ways of viewing art, this film provides an opportunity for viewers to safely see the artwork, hear the voices of artists, scientists, and community leaders and gain an inside perspective on the exhibit.

Produced by the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society at NAU in collaboration with the Flagstaff Arts Council. With funding support from the National Endowment for the Arts, National Science Foundation, and Arizona Humanities.

Parched: The Art of Water in the Southwest was produced by the Flagstaff Arts Council in Partnership with NAU Center for Ecosystem Science and Society, and Coconino Plateau Watershed Partnership. The project was made possible through grants provided by National Endowment for the Arts, National Science Foundation, and Arizona Humanities.

2021 Amerind Museum, Dragoon, AZ

2022 Natural History Institute, Prescott, AZ